It’s an easy mistake to make. When you look at a graph of the number of public firms in the U.S. between 1980 and 2020, and you see a 50 percent decline after 1996, it’s natural to think that companies don’t see the benefit of going public in the U.S. It causes one to question the competitiveness of the U.S. economy and stock markets.

Tuck Centennial Professor of Finance, Bjorn Espen Eckbo studies corporate finance, with a particular emphasis on transactions in the market for corporate control, how firms raise capital to fund investments, capital structure choice, and issues in international corporate governance.

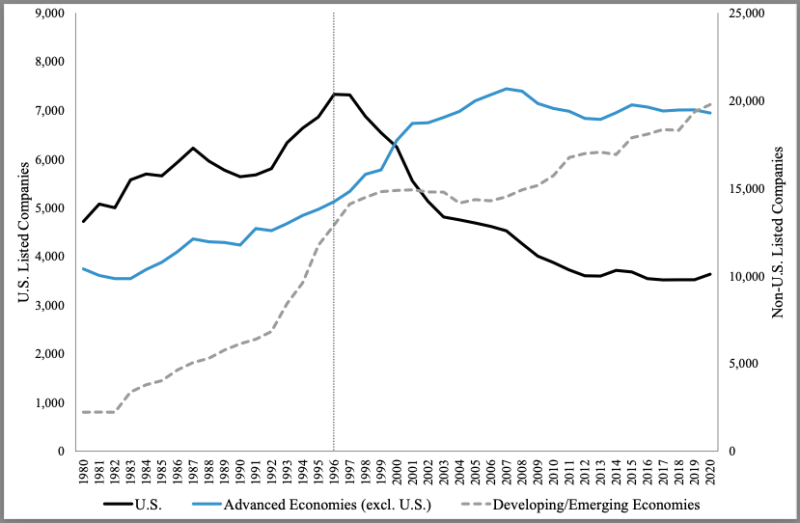

And the picture only seems to get more dire when you compare the number of U.S. listed firms to the aggregate number of firms listed in foreign countries. Everywhere but the U.S., the trend appears to be the opposite: a growing number of firms are listed on public exchanges. The U.S. had more than 7,000 public firms in 1996, and in 2020 it had less than 4,000. Meanwhile, the tally of public firms in non-U.S. advanced economies rose from about 4,000 in 1996 to 20,000 in 2020. And in developing/emerging economies, the number of public firms went from less than 1,000 in 1996 to 20,000 in 2020.

There has been much handwringing about this situation. In 2018, Robert Jackson Jr., the commissioner of the SEC lamented, “[when] … our most exciting young companies … raise private capital rather than go public, retail investors are left out of a significant part of the Nation’s economic growth.”

But Espen Eckbo, the Tuck Centennial Professor of Finance, wasn’t so sure this narrative was correct. So, he and Markus Lithell (a PhD student from the Norwegian School of Economics who visited Tuck and is now an assistant professor of finance at Virginia Tech), decided to do a more thorough accounting of public firms and, crucially, the companies that those firms acquired or merged with. Their findings appear in their paper “Merger-Driven Listing Dynamics,” which was published in 2023 in the Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis.

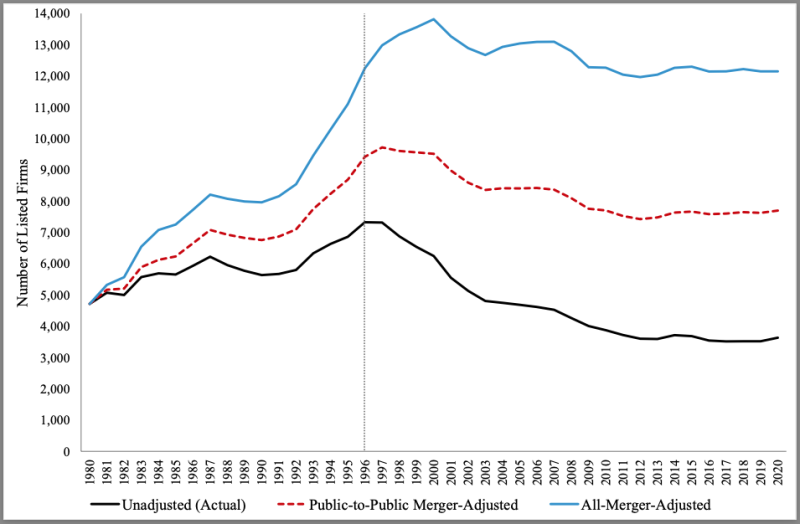

The phrase “listing dynamics” in the title of the paper refers to the different reasons why the number of public companies rises and falls over time. The number rises if a private company does an initial public offering (IPO) or if a public firm spins off another public company. Observers generally view this rise as a good thing for the economy. But does that mean it’s always a bad thing when the number falls? Not necessarily. A decline in the number of public firms could be due to bankruptcies or public firms being bought by private investors (bad for the markets), but it could also be the result of two public firms merging into one. Those mergers happen so firms can achieve synergy gains, which can reach into the hundreds of millions of dollars per merger (good for the markets). That sort of merger activity is not counted in the official tally of listed firms, so Eckbo and Lithell took the time to find the mergers and create a “merger-adjusted” list of public companies. That list includes publicly listed companies, plus private and public companies that merged with public companies (some of the private targets could otherwise have entered the public market through an IPO).

To illustrate what’s going on here, Eckbo created three graphs:

The first one is titled “Aggregate Stock Exchange Listing Counts Around the World (1980-2020)” and presents the official count of public firms, showing a steep decline for the U.S. and a steady incline for a total of 73 other countries (covering 90+ percent of world GDP).

Aggregate Stock Exchange Listing Counts Around the World (1980-2020)

The second graph is “Actual and Merger-Adjusted U.S. Listing Counts (1980-2020).” This shows how the merger adjustment, which explicitly recognizes that any firm is a portfolio of itself and the targets it acquires over time, erases the drop in the total number of U.S. adjusted-listed firms. The top line adds both public and private targets of public acquirers back into the listing count, while the middle line adds back public targets only.

Actual and Merger-Adjusted U.S. Listing Counts (1980-2020)

The third graph is titled “Contribution of U.S. listed firms to economic activities” and shows how productive the actual (unadjusted) number of U.S. listed firms are today: although the number of listed firms is cut in half after 1996 (from about 8,000 to about 4,000), they contribute as much or more to employment, GDP, R&D and patents as all listed firms prior to 1996.

Contribution of U.S. listed firms to economic activities

“Most of the time, just about everybody who hasn’t thought about merging blames the U.S. decline in listed firms on a lack of IPOs,” Eckbo says. “While it’s true IPOs have dropped since 1996, when you include the mergers, you see a very different and rarely recognized picture: firms listed on the three major U.S. stock exchanges have been able to attract private targets and retain public targets under public ownership to such an extent that it outweighs the IPO decline.”

Most of the time, just about everybody who hasn’t thought about merging blames the U.S. decline in listed firms on a lack of IPOs,” Eckbo says. “While it’s true IPOs have dropped since 1996, when you include the mergers, you see a very different and rarely recognized picture.

— Espen Eckbo, Tuck Centennial Professor of Finance

Finally, Eckbo and Lithell also examine the listing dynamics of each country hidden underneath the aggregate number of firms listed outside of the U.S. in the first graph above. Surprisingly, over the total sample period, 80+ percent of those country-specific stock exchanges also experience a nearly 50 percent drop in the number of listed firms—much as in the U.S. but in different years (so the aggregation across countries levels out those drops). Moreover, outside of the U.S., those dramatic listing declines are not countered by listed firms acquiring public or private targets.

“This evidence shows that the U.S. stock exchanges offer an important relative listing advantage over other countries: Access to a market for corporate control that promotes complex corporate takeover deals causing significant wealth gains for both acquiring and target firms,” Eckbo says.