Slaughter & Rees Report: What Prince Taught Us About the Global Economy

Towards the end of one of his early hits “1999,” Prince hauntingly foretold that, “life is just a party and parties weren’t meant 2 last.”

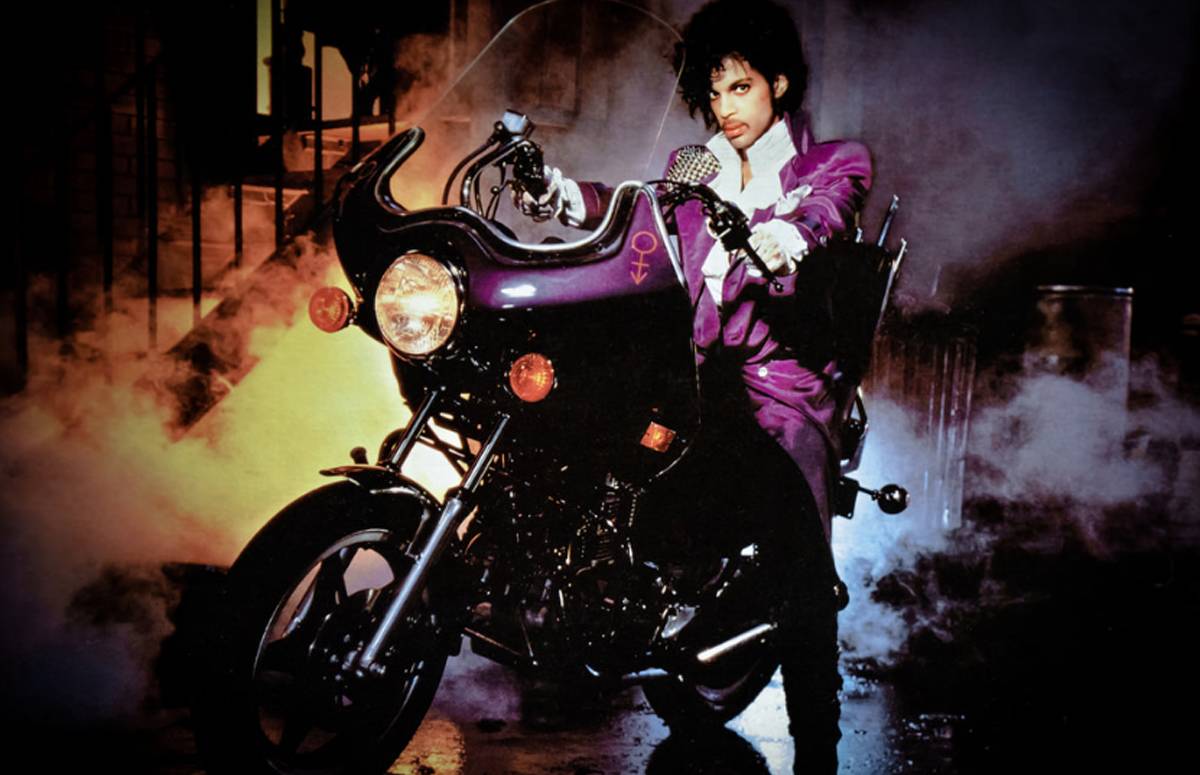

Towards the end of one of his early hits “1999,” Prince hauntingly foretold that, “life is just a party and parties weren’t meant 2 last.” Last Thursday the world was shocked to learn that Prince, one of music’s most prolific and talented artists ever, was unexpectedly found deceased in an elevator at his Paisley Park estate in Chanhassen, Minnesota.

This news hit especially close to home to one of your correspondents who grew up in the next-door town of Minnetonka, whose lake was forever memorialized in Prince’s blockbuster movie and album Purple Rain for its “purifying waters.”

Prince’s passing has triggered a flood of wistful commentary. President Obama said in a statement, “Today, the world lost a creative icon … nobody’s spirit was stronger, bolder, or more creative.” Presidential aspirants and other policy makers might not have Prince top of mind. But for at least a moment, he should be. This is especially true around the pressing topic of income inequality in today’s global economy. In fact, Prince taught us three important lessons that should be heeded on the campaign trail and in the corridors of power.

First: talent—and thus economic growth—can arise from anywhere in a way that policy makers can rarely predict. Prince at the end of his life was widely revered as one of the most talented musicians ever. The obituaries of the world (here, here, here) rightly read more like hagiographies. Prince’s abilities were legion and seemingly unbounded. Part of what made him so remarkable was how skilled he was at basic guitar playing. ZZ Top lead guitarist Billy Gibbons gushed that, “sensational is about as close a description of Prince’s guitar playing as words might allow … if afforded the luxury of actually seeing Prince perform … we’d be looking for other superlatives. Because it’s almost got to the point of defying description.” This alone would have put him in rarefied air. But added to that was such creativity, flair, and vision—across so many areas, all honed over decades by an indefatigable work ethic. On so many of his major recordings he composed, arranged, performed, and recorded all music and all instruments.

And yet, Prince came from very modest beginnings. His family was blended, somewhat troubled, not well-to-do; he attended public schools in inner-city Minneapolis. Classmates even then were afforded glimpses of what lie ahead. But Prince did not hail from a wealthy and distinguished musical pedigree; he did not attend music summer camps and enrichment programs and The Julliard School. On paper, few central planners would have wagered on Prince. Yet his abilities would have proven them all wrong.

Economic policy makers should learn from this both humility and inspiration. Be humble at how little we know about from where talent and all its attendant economic benefits will spring. Be inspired to recognize how much talent you can unleash if you strive to create opportunity—as widely as possible for as many as possible.

Second: some degree of income inequality is inevitable. Prince’s accomplishments were legion. Seven Grammys and 32 Grammy nominations. A Golden Globe. An Oscar. An estimated 100 million records sold worldwide. Successful concert tours that spanned the globe. Induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. All of this accomplishment put Prince deep into the one percent. His net worth is estimated to be at least $300 million, spanning assets including his 55,000-square-foot Paisley Park estate.

The policy lesson here is that some amount of income inequality will be inherently driven by inequality in individual talent—even as that unequal talent massively expands economic output and welfare around the world. Barring a dark future like that foretold in Kurt Vonnegut’s Harrison Bergeron, people will always have unequal abilities that lead to unequal distribution of income and wealth.

Third: globalization and technological change can dramatically expand the scale of the talented—in ways that boost both output and inequality. Prince came into his own as the world was coming into the information-technology revolution. The album 1999 was released in 1982, just after that radical technology innovation called MTV celebrated its first birthday (and just after the late Sherwin Rosen published his seminal American Economic Review paper germane to today’s missive, “The Economics of Superstars”). Yes, Prince often was ambivalent about IT, in part because of his desire to control the distribution of his artistry. Yet the ability of IT to spread his works across the globe—combined with a burgeoning worldwide demand for such artistry thanks to rising incomes in the BRICs and far beyond—created a global fan base that drove his album sales, concert attendance, and overall interest.

In an imaginary world absent the IT revolution and globalization of the past decades, Prince would have still rocked First Avenue and Seventh Street Entry in the Twin Cities—but not much beyond. In our real world he became a global icon thanks in large part to globalization and technology advances. When people and companies can scale their talents (and their investments therein) in ways that the world now permits, growth and inequality—especially at the very top—can surge. This same dynamic of global scalability explains the high incomes of those talented in many other occupations such as athletes, bankers, consultants, and lawyers. Prince’s global media hits are the artist’s equivalent of the alpha-seeking hedge-fund-manager’s assets under management.

In the opening lines of “Let’s Go Crazy” from Purple Rain, Prince hauntingly described the afterworld as “a world of never-ending happiness/U can always see the sun, day or night.” We hope that wherever and whatever the afterworld might be, Prince is indeed enjoying some deserved sunshine.

RIP, Prince Rogers Nelson.