Seeds of Change

In the 1960s, Tuck underwent a shift every bit as significant as the monumental societal changes playing out on college campuses across the country. We just didn't realize it at the time.

John Hennessey was giving a talk in California when he received the news.

At Kent State University in Ohio, National Guard troops had fired into a crowd protesting the U.S. invasion of Cambodia. Four people lay dead, and at campuses across the country students were taking to the streets in spontaneous expressions of outrage, bewilderment, and fear. Hennessey had been dean of the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth College for less than nine months and knew intuitively that the next few days could be the most challenging in the school's 70-year history. He took the overnight flight to Boston and drove without sleep to Hanover, where, at 11:00 on the morning of May 6, 1970, he addressed the students.

To Hennessey, it felt as if the social upheaval of the entire preceding decade—the Civil Rights movement, internationalism, women's equality, environmentalism—had suddenly come to a head. "The 1960s were dramatically alive," recalls Hennessey, who served as dean from 1968 to 1976. Universities were at the nexus of this jarring cultural shift, one result of which had been a fundamental change in the way that college students related to their institutions. Gone were the dress codes and parietal rules, the very notion that colleges should act in loco parentis toward students. That authoritarian relationship had been replaced by a new student-faculty dialogue, frequently punctuated by demonstrations and sit-ins.

At Tuck, these changes had largely taken place beneath the surface, but the events in Ohio brought them dramatically to the fore. A few days after Kent State, MBA students from several elite schools invited faculty and deans to join them at an open-air meeting at Wall Street in New York—a far more sober affair than the cathartic protests happening elsewhere. "It was kind of a transmutation from the heavy undergraduate takeovers, protests, and anger into a more mature reflection," Hennessey says. "We felt the national conversation would improve if we became more vocal."

Last fall, at the 40th reunion of Tuck's class of 1970, Hennessey recalled that dynamic time with members of the class. "They remember very vividly," Hennessey says. "They saw it as a learning opportunity, and that gathering together with Tuck students, other MBA students, and with the undergraduates at Dartmouth was a warm moment of real progress."

The Vision

The dramatic weeks after Kent State were an anomaly at Tuck, which was in the process of a gradual but very significant shift from a professional school for Dartmouth men into a modern MBA program with a global reach. Hennessey's predecessor, Dean Karl Hill, set the school on this trajectory in 1957, and the effort would continue throughout Hennessey's tenure as dean.

At the heart of this strategy was a steady increase in the proportion of students from universities other than Dartmouth and an emphasis on modern business practices, including the first computer classes at an American business school. The transition included a rise in the numbers of students with previous experience in business and the military and a passionately felt commitment to the inclusion of minorities and women.

All of these changes are critical to Tuck's current excellence and identity. Taken together, they represent a shift in the school's culture every bit as significant as the monumental societal changes that were taking place at the same time. Yet, as is often the case when history is being made, many of the protagonists did not realize they were living in such extraordinary times.

"The thing about the 1960s," says Fred Schauer D'67, T'68, "is that they didn't arrive in Hanover until the 1970s." Tuck occupied a quiet corner of a small college in a small New England town. In the mid-1960s, Hanover had one television station. The interstate was still pushing slowly up the Connecticut River Valley and Boston was four hours away. Long after the counterculture had reached a rolling boil in Berkeley and Cambridge, Tuck students still went to class in sport coats and ties.

Charlie White T'68 arrived on campus in the fall of 1966 clad in an olive-drab uniform and a rather conspicuous bandage on his head. The 27-year-old Army captain had been banged up in South Vietnam on a Thursday and signed in to Tuck the following Tuesday. He hadn't worn his uniform to make a statement; he just didn't have any civilian clothes.

If everyone had been like me, right out of undergraduate, it would have been nowhere near the experience. I felt it was hugely to my advantage to be with a more mature crowd"

— Harvey Bundy, T'68

White had gone to Boston College as an ROTC student, finished at the top of his class in 1961, and applied to two graduate schools, Tuck and Yale Law. Accepted at both, he deferred his active-duty obligation to study law in New Haven. "I didn't even send Tuck a letter," he says. "I just didn't show up."

By the time he finished law school, the United States was deeply embroiled in Vietnam. White arrived in-country in 1964 and saw combat as a field-artillery officer. When I get out of this place, he wrote his wife Marie, we'll go to Hanover. That will be our reset. White then wrote a long-overdue letter to Tuck, enquiring whether his five-year-old acceptance was still valid. The school not only renewed the offer, it hired Marie, who lived in the married-student housing at Sachem Village and worked as an editor at Dartmouth Alumni Magazine while her husband finished his tour in Vietnam.

White quickly bonded with other married students. They had in common their age and marital status, but in other ways they were strange bedfellows. Harry Howell had been an all-Ivy hockey player at Harvard. Ed Glassmeyer had been a Marine officer in Vietnam, while his close friend, Harvey Bundy, had chosen Tuck over Harvard Business School in part to avoid the war—leaving school for a year after graduation to meet Harvard's requirement for prior work experience would have exposed him to the draft. (Bundy had a unique perspective on the war: his uncles William and McGeorge Bundy were among the chief architects of the American escalation in Vietnam, and two of his Yale roommates—including future U.S. Senator John Kerry—had enlisted immediately after graduation.)

"I was the bright, nerdy kid," Bundy says. "I had an opinion on anything and was willing to take on anyone." Bundy excelled in his coursework and fed off the energy and experience of his study-group partners—Bundy, Glassmeyer, and Howell would eventually graduate at the top of their class. Bundy feels that the academic work at Tuck was easier for students who came straight from a rigorous undergraduate program than for those who had spent the previous few years outside school. The older students, however, excelled in the intangibles—the focus, business savvy, and life experience that can't be learned in a classroom. "If everyone had been like me, right out of undergraduate, it would have been nowhere near the experience," Bundy says. "I felt it was hugely to my advantage to be with a more mature crowd."

Dean Karl Hill knew the value of experience and diversity when he came to the deanship. In the class of 1962, 55 of the 94 students were "3/2s," undergrads who had started at Tuck during their fourth year at Dartmouth. Six more from that class were "Dartmouths," who had entered Tuck immediately after earning their Dartmouth degrees. Barely more than one-third of the class came from other universities, and only 14 percent were married. Importantly, just 77 of the 94 received their Tuck degree. Because they earned their undergraduate degree at the end of their first year at Tuck, many 3/2s opted not to continue at Tuck.

Just 12 years later, 3/2s comprised only 18 percent of the class of 1974. Thirty-nine percent of that class had prior work experience, including 23 percent who had been in the military. Nearly a third were married, and 92 percent ultimately received their Tuck degrees.

"Both educationally and in terms of career opportunities, it made sense to admit students with work experience," says Penny Paquette T'76, assistant dean for strategic initiatives. "Today, we are one of the few business schools that have not started to admit a proportion of their students straight out of [undergraduate] school." While the transition was not complete until the mid-1990s, it was rooted in—and affirmed by—the changes Dean Hill set in motion in the early 1960s.

George Trumbull T'68 came to Tuck straight out of Dartmouth, where he had played on the undefeated 1965 football team. A middle-class kid with a gregarious, devil-may-care attitude, he formed a fast friendship with Charlie White, whom he describes as something of a mentor. "Put it this way: I got more out of Charlie White than he got out of me," says Trumbull. White isn't so sure.

"I saw a joie de vivre, a happy, fun outlook on life, that I learned from George," White says. "I was in a slow-motion changing of gears from Vietnam. Coming back from there, you're wired differently. You're in a different world." White calls his time in Vietnam the worst of his life. His time at Tuck, thanks to the deep friendships he formed there, was the greatest. Even as the anti-war movement gathered steam, White felt at home in Hanover. He didn't feel as if he had to explain himself. "Karl Hill was a wonderful dean. He could see I was different—mainly because I had a bandage on my head—and Karl called me aside and said, ‘Look. Take your time and adjust.'"

The Pioneers

As fruitful as these interactions were, something clearly was missing. Like most business schools at the time, Tuck was all-white, and all-male. Dean Hill had long been determined to integrate Tuck, and Hennessey, whose brief tenure as associate dean included expanding the schools from which Tuck attracted applicants, would be an enthusiastic partner in the effort. The first African American students at Tuck enrolled in 1964. A few years later, when Hennessey was asked to assume the deanship, he made the admission of women a prerequisite to his acceptance. Tuck's first female student, Martha Fransson T'70, arrived on campus in September 1968, Hennessey's first year as dean.

"There was a feeling that it's time. It's time we have the Civil Rights Act. It's time we create opportunities for people who didn't have them in the past," says Hennessey, who in 1968 would become the founding chair of the Council on Opportunity in Graduate Management Education, established with a large grant from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation to increase the flow of minority students to the five most selective MBA programs.

Dartmouth had been recruiting black students for a number of years (Trumbull had roomed with an African American player on football road trips), and the school's trustees were firmly behind the integration of Tuck. The question now became how to attract qualified students at a time when Tuck was still known primarily as a school for Dartmouth men.

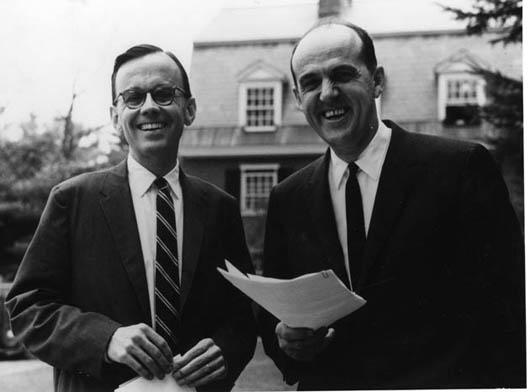

As part of their long-term effort to increase the number of non-Dartmouth students at Tuck, the deans had been making regular recruiting visits to Yale, Harvard, Princeton, MIT, and other schools. In 1964, Hill and Hennessey brought the same approach to the recruitment of African American students. They drew up a list of the 10 top historically black colleges, and each committed to visiting five of them.

"We began to recruit students, and to do that we had to explain who we were to the faculty and advisors. We had a conference of faculty from the historically black colleges in February, so people from outside New England would understand what winter is like in Hanover," Hennessey says. The deans knew the breakthrough students would, like the current Tuck students, have to be exceptional people, possessing both the intellect to thrive in a very challenging academic environment and the temperament to deal with immense expectations.

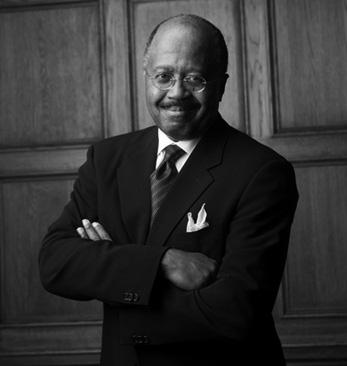

Herbert Kemp T'66 had never heard of Tuck, but he had excelled in business classes at Morgan State College—now Morgan State University—in Baltimore, and at the urging of faculty who had met with Dean Hill, he applied to Tuck. At his graduation, Morgan State President Martin D. Jenkins announced to great applause that Kemp would be attending the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth College, on a scholarship. "My parents were in the audience," Kemp says. "It was the proudest moment of my life."

Now the hard work began. The scholarship was not a full ride; Kemp also received a loan and a work-study job. "I was working in the cafeteria three times a day," he recalled. "The only resources were in the Tuck library, and the first one there gets the books. I was always last."

He admits to having felt like an outsider at Tuck, not because of his race, but because he lacked Dartmouth connections. The best 3/2 and Dartmouth students knew whom to team with, and the married students had formed their own high-powered study groups. Kemp felt like the last player chosen in a pickup game. He struggled personally and academically.

His experience shows just how challenging it is to be a pioneer, and how delicate a project the integration of Tuck was. Though Kemp and another African American student, Richard Hearn, arrived in Hanover just two years after James Meredith's admission to the University of Mississippi sparked widespread rioting, there was no such ugliness at Tuck. Indeed, there was very little acknowledgement that anything extraordinary was taking place, which was both a testament to Hill and Hennessey's careful management of the process and, in a strange way, part of the problem.

"They were just our classmates," recalls Trumbull. Mickey Beard D'67, T'68, a 3/2 who was quarterback of the Dartmouth football team, played intramural basketball with Kemp and invited him to fraternity parties. Yet Kemp didn't think of himself as ordinary student; he felt tremendous pressure to succeed, particularly after Hearn chose not to return to Tuck for his second year (he later graduated with the class of 1970).

"Being African American in Hanover in the '60s was quite a unique experience," Kemp says. "Even getting a haircut was a challenge." Dating, in the context of the time, was out of the question. In the same way that Dean Hill had quietly helped White through his transition from Vietnam, he worked behind the scenes to ease Kemp's path. When he learned that Winter Carnival weekend and similar events exacerbated Kemp's social isolation, Hill arranged a travel stipend for Kemp's college sweetheart—now his wife—to visit from Washington, D.C. "Dean Hill and Dean Hennessey were absolutely fabulous," Kemp says. "They listened to me; they understood. I felt nothing but welcome from them."

Kemp, who went on to a successful career in marketing and advertising, now heads a marketing consultancy specializing in helping Fortune 500 companies connect with African American consumers. In a sense, he does the same for Tuck, returning regularly for diversity weekends, where he shares his story with minority students considering the school. "Tuck is one of the best things I have ever done," he tells them. "It was also one of the toughest things I have ever done. It has made such a difference in the quality of my life. I would do it again."

Dean Hennessey would repeat the process as well. In 1968, two years after Kemp graduated, the first woman matriculated at Tuck. The process would be fraught with many of the same cultural and logistical hurdles that Kemp and Hearn had confronted. From an administrative perspective, it was even more challenging.

When he made admitting women a condition of his accepting the deanship in November 1967, Hennessey says, "there was a furious debate, particularly in the Ivy League schools, about whether coeducation was wise or not. It wasn't clear even on a practical level, how to [introduce women to] institutions that had been all-male for so long. At Tuck, we just said we will do it. It was necessary to make coeducation work."

Tuck became something of a coeducation experiment within the larger Dartmouth community. From Hennessey's perspective, though, the result was never really in doubt. Every Tuck class since 1972 has included women. When Paquette arrived with the class of 1976, women made up 12 percent of the class. Today they comprise 35 percent.

Also in this period, Tuck was becoming more international. Students from abroad had been a rarity before the mid-1960s; the class of 1968 had just three international students. The class of 1970 had eight, and the '72s had 11, or about nine percent of the class. The percentage would hover around 10 or 15 percent until the mid-1990s, when it again trended upward at the urging of Dean Danos. Recent Tuck classes have averaged about 35 percent international students, Paquette says.

"We were beginning in the late '60s and early '70s to see all those transitions occur, and now I think Tuck has achieved, in my mind, a very good balance," says Trumbull. "Part of the Tuck education is the interaction with your classmates. That is as much a part of the education as what you get in the classes."

At the same time that the composition of the student body was becoming increasingly diverse, the curriculum at Tuck was becoming more modern, with increased emphasis on international business, technology, and ethics.

The Future

At the same time that the composition of the student body was becoming increasingly diverse, the curriculum at Tuck was becoming more modern, with increased emphasis on international business, technology, and ethics. Nothing, though, was so forward-looking as the introduction of computer classes at Tuck, where, starting in 1966, first-year students were required to learn how to program in BASIC, a language developed by Dartmouth mathematicians Thomas Kurtz and John Kemeny, who would become president of the college in 1970.

At that time, computers were rare in liberal-arts institutions. The behemoth machines were the exclusive province of mathematicians and physicists—massive scientific instruments dedicated to cracking the mysteries of the universe. These were not tools that ordinary students—and certainly not business students—would use on a daily basis. But General Electric had set out to challenge IBM's dominance in the fast-growing computer field, and company executives saw an opening: What if they were to build a computer on the campus of a liberal-arts institution? The idea, explains Charlie White, was to explore the potential of computers outside the hard sciences. "At that time, John Kemeny, who had been Einstein's research assistant at Princeton and was a genius in his own right, was at Dartmouth in the math department," says White. "They thought, here's a liberal arts college with an outstanding mathematician. Let them play with the machine and see what it can do."

What the machine did, among other things, was quantitative analysis, a type of applied science that would radically transform the business landscape throughout a period roughly paralleling the careers of Tuck graduates of the late 1960s and early 1970s. In the GE-635 computer, a colossus that filled a building, Tuck saw an equally large opportunity to differentiate itself from other business schools.

"It seems like an odd thing to make an MBA learn to program. But it meant that I was comfortable with computers all through my business career," Bundy says. "I could understand how the world was changing in a way that a lot of people coming out of business schools at the time wouldn't have had the skills to do."

Today, the world's richest firms compete for the fastest supercomputers and most sophisticated algorithms. Tuck students and faculty were at the forefront of this revolution. In the summer between his first and second years at Tuck, White worked with an entrepreneurial company that applied the computer time-sharing developed at Dartmouth. He joined the firm full time when he graduated in 1968. "We were a dot-com before there were dot-coms," White says. "One of our clients was Harvard Business School."

The computer was an instrumental piece of Tuck's rise to the top ranks of business schools, but the demographic changes were equally important. When Hennessey left the deanship in 1976, the long-reaching changes Dean Karl Hill had set in motion in 1957 were complete. Tuck was an international business school, with a curriculum and student body reflecting the diversity and talents of a rapidly flattening business world. By 1983, 90 percent of Tuck students had prior work or military experience; since 1995, when Paul Danos assumed the deanship, every new Tuck student has had some relevant experience before arriving at Tuck. These changes were a necessary precursor to Tuck moving center stage—a transition that was ultimately completed during Danos' tenure, says Paquette.

In some ways, says Bundy, Tuck has undergone more changes since Danos arrived than in the intervening 20 years. "Paul put Tuck on the map more than anyone else has," he says. However, the vision of Deans Hill and Hennessey, and the changes they brought about—the shift to an older, more experienced student body, the admittance of women and minorities, and the increase in international students—were crucial to establishing Tuck so firmly in the upper echelon of MBA programs.

The 1960s was a time of dynamic, often rending change in the country and at Tuck. But with the benefit of 40 years of hindsight, we know now that it was for the best.

*This article originally appeared in print in the fall 2010 issue of Tuck Today magazine.