With COVID-19 Looming, Tuck Students Address an Oxygen Shortage in Haiti

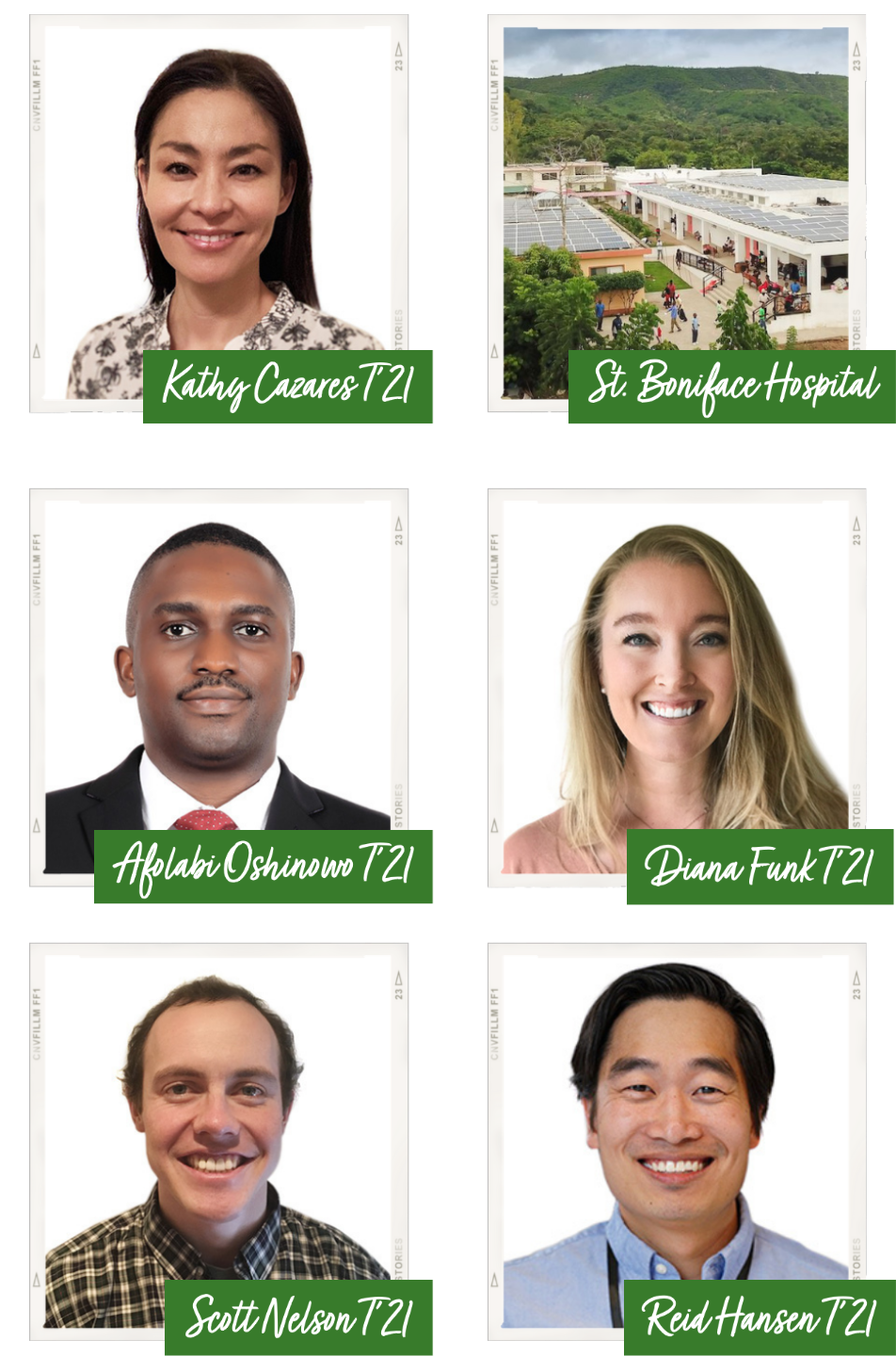

A team of five Tuck students enrolled in the OnSite Global Consulting course created a sustainable model for oxygen distribution in Haiti’s Southern Peninsula.

Students partnered with the Boston-based global health care design and engineering nonprofit Build Health International (BHI) to design a sustainable model for oxygen delivery in Haiti.

St. Boniface Hospital, an essential 180-bed facility that serves Haiti’s Southern Peninsula, has transformed the quality of health care in its community since it opened in 1992.

As the only tertiary care center in the area, the hospital has seen a steady rise in the demand for therapeutic oxygen, which is used to treat a variety of patients such as newborns, children, women in childbirth, and people needing surgery. Then the COVID-19 pandemic hit the island, and Haiti’s oxygen needs climbed even higher. Every three to four days, the hospital sends a truck on a seven-hour round-trip journey over rough roads to Haiti’s capital of Port-au-Prince to pick up oxygen at a cost of $25 per cylinder. Sometimes the roads are closed, due to frequent civil unrest, so the truck goes to a supplier in Miragoane, which is closer but charges nearly twice as much.

"All of us are involved in health care and we’re all very much dedicated to improving health care in any way we can," says Kathy Cazares T’21 of the student OnSite team.

This fall, as the COVID-19 situation in Haiti grew worse, a team of five Tuck students had a chance to help. For their OnSite project, they partnered with the Boston-based global health care design and engineering nonprofit Build Health International (BHI) to design a sustainable model for oxygen delivery in the southern part of the country.

In 2016, BHI built a 780-panel photovoltaic system at St. Boniface, which is not connected to the electrical grid, thus guaranteeing the hospital a reliable, affordable, and clean source of energy. Since then, BHI worked with Tuck students on a supply chain project at St. Boniface. “We were really trying to come up with the right project for Tuck again,” says Jim Ansara, BHI’s director.

When Ansara pitched the oxygen project to Tuck, he found an eager and experienced team composed of T’21s and MD/MBAs Kathy Cazares and Diana Funk and T’21s Reid Hansen, Scott Nelson, and Afolabi Oshinowo. “All of us are involved in health care and we’re all very much dedicated to improving health care in any way we can,” says Cazares. While Cazares and Funk, fellows at the Tuck Center for Health Care, are studying to become doctors, Oshinowo is a licensed medical doctor in Nigeria who served patients during that country’s Ebola crisis. Hansen, also a fellow at the Center for Health Care, and Nelson came to Tuck after spending years in health care administration.

In the United States and most developed nations, oxygen is readily available to hospital patients through a system of pipes that connect to each bed or room. In Haiti, however, therapeutic oxygen is created through a process called pressure-swing adsorption, where a powerful compressor pumps ambient air through a filter to separate the oxygen from the nitrogen. The remaining gas, which is 94-96 percent pure oxygen, is then compressed and stored in high-pressure metal cylinders. These cylinders are then transported to hospitals for use.

Staff pictured outside of the St. Boniface Hospital in Fond-des-Blancs, Haiti, which treats more than 137,000 patients in a single year. Photo courtesy of Health Equity International.

This process is energy-intensive, and since St. Boniface is already using solar power to generate electricity, the Tuck students examined the possibility of adding more solar panels to the facility to power an oxygen plant. The main questions were whether this type of capital investment would be financially feasible for the hospital, and how best to arrange the system so the entire Southern Peninsula could benefit from it. In order to answer these questions, the students asked many of their own—in more than 20 interviews with stakeholders such as local doctors, engineers, and health care NGOs. “They really approached the project with humility,” says Ansara. “This allowed them to engage with people deeply and get a lot of good information, which is especially important in a case like this, where you’re dealing with a lot of cultural and historical complexities. Haiti is as complex as it gets.”

What they found through their interviews is that developing a project like this in Haiti requires a lot of flexibility and creativity. Models and systems that work in more developed countries don’t always succeed in Haiti. “What was most eye-opening from our interviews is that you can’t just go there and make things perfect,” explains Cazares. “You’re really working within a system where there are so many challenges. You have to embed what you’re doing within the actual practicalities of what’s happening on the ground.”

Using cost and demand models they learned from the core Analytics courses, the students concluded that a solar-powered oxygen plant at St. Boniface would be a cost-effective system in the long run, breaking even in 10 years and providing oxygen cylinders for $18 instead of $25. But they didn’t stop there. In order to ensure that the oxygen could get to other locations in the Southern Peninsula, the students came up with the idea of a hub-and-spoke system for distribution, where a depot would be situated in the city of Les Cayes to supply other hospitals in the area. “It’s not perfect,” admits Cazares, “but it’s going to lower costs and increase access, and hopefully provide opportunities for therapy for people who need it.”

What was most eye-opening from our interviews is that you can’t just go there and make things perfect. You’re really working within a system where there are so many challenges. You have to embed what you’re doing within the actual practicalities of what’s happening on the ground.

Kathy Cazares T’21, MD/MBA

The students reported their findings and recommendations to BHI in a 56-page presentation that Ansara remarked was as “good a report we have seen on issues and problems like this in low-resourced countries. The World Bank pays consultants mid-six-figure sums to produce reports and white papers that are half as good as this.” In fact, Ansara thought the report was so professional and insightful that he shared it with the Every Breath Counts (EBC) Coalition, a group of NGOs such as the World Health Organization, Unicef, the Gates Foundation, Partners in Health, and many others, who are working on access to oxygen in the developing world. The EBC, in turn, invited the Tuck team to present its findings during their weekly conference call at the beginning of January.

With the technical details of the project settled, Ansara can now turn to the harder part: fundraising. USAID, the U.S.’s international development agency, has proposed sending funds to the Haiti Ministry of Health to work on oxygen distribution, which will build momentum among other organizations devoted to healthcare in Haiti. Cazares is optimistic the St. Boniface project will come to life within the next year.

For Ansara, a lot of the credit will go to Tuck. “Their report really adds a lot of legitimacy to the proposal,” he says. “It’s not a group of global health engineers and advocates saying it’s possible. It’s Tuck—it means something.”