The Education Technology Revolution

It’s graduation season at colleges and universities here in the United States. Yesterday at Dartmouth, about 1,800 students earned various degrees—including 266 newly minted Tuck MBAs. Graduation traditionally brings celebration: of a hard course of study completed, and of a job offer well earned.

In recent years, however, graduation increasingly brings anxiety. All is not well with American higher education. Many of you know the anecdotes: kith or kin who borrowed heavily to pursue a degree, only to find that the next step was to underemployment as a barista—or, even worse, to unemployment and back home on mom and dad’s basement couch.

The more systematic data are even more sobering. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York estimates in a recent report that total student debt in America had reached $966 billion at the end of 2012—an amount that has nearly tripled in just eight years, driven by a 70 percent increase in both the number of student-loan borrowers and the amount each borrower owes. Last month, McKinsey released a report based on a recent survey of 4,900 recent college graduates in America. The report, “Voice of the Graduate,” speaks of “a cry of help—an urgent call to deepen the relevance of higher education to employment and entrepreneurship so that the promise of higher education is fulfilled.”

How plaintive is the cry? Sit down. Forty-two percent of graduates of four-year colleges are in jobs that do not require a four-year degree, and 41 percent are not working in the same field they desired before graduation. If granted a mulligan, 53 percent of all graduates would select a different major, a different school altogether, or both. Liberal-arts graduates fare the worst. According to the McKinsey report, “they tend to be lower paid, deeper in debt, less happily employed, and slightly more likely to wish they’d done things differently.”

While you remain sitting (or curled up in a ball), let us share two optimistic thoughts. The first is that, although all is indeed not well with American higher education, much still is. Some of this cry likely reflects the cyclical damage of the Great Recession. College graduates still fare much better in the labor market than those without a college degree, with higher average earnings and lower average unemployment rates. And America’s best schools remain among the world’s best. This is especially true in the STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) fields, which are the source of so much innovation and productivity growth. Today in engineering, all of the world’s top 10 universities are in the United States, as are nine of the top 10 in life sciences, and seven of the top 10 in both natural sciences and mathematics.

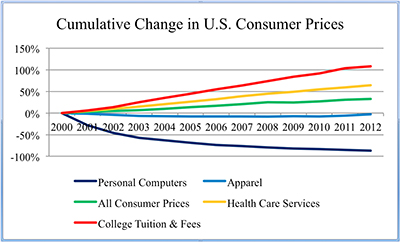

The second reason for optimism is that higher education has vast opportunity to innovate and address shortcomings in areas such as quality, cost, and relevance. Just how vast can be seen in the chart below, which documents the cumulative change from 2000 through 2012 in U.S. prices for five major industries (as measured by the U.S. Consumer Price Index of the Bureau of Labor Statistics). To read this chart, keep in mind that high-innovation, high-productivity-growth industries tend to be ones with falling, not rising, prices.

Start at the bottom, with personal computers, which have experienced a stunning price decline of almost 87 percent. This industry is among the world’s most technologically innovative, in part because of how globally engaged it is. The net combination of these dynamic forces—what is commonly called the IT revolution—has long provided consumers with new and better products: massive innovations that mean for consumers dramatic price declines. Next is apparel, with a price decline of about 3 percent: quite innovative, actually, again in large part because of its global engagement. Then comes the overall CPI, rising a bit more than 32 percent, and health-care services—an industry rising just over 64 percent. (Footnote: that two-x differential of health costs over all costs is, if left unchecked over the next generation, what threatens U.S. fiscal solvency.)

That leaves the red line: college tuition and fees, rising more than 108 percent. We would like to tell you this increase has been entirely driven by strong demand for a product of consistently high quality. This may be part of the story, but students crying for help suggest that strong demand isn't the whole story. Productivity is hard to measure in education, but what measures scholars use do not reveal anything near IT productivity-growth rates: e.g., many college classrooms today look like college classrooms 100 years ago.

The future of U.S. higher education can be much brighter. Schools that figure out how to be more productive—how to innovate what they teach to whom and how—will discover a surge in interest among students, parents, and employers. The emergence of MOOCs—massive online open courses—is an example of this potential. Indeed, innovative schools might catalyze education’s version of the IT revolution. Call it the Education Technology, or ET, revolution. For all those anxious students, parents, and educators alike, let’s bring it on.

Articles © 2013 Matthew Slaughter and Matthew Rees. All rights reserved.

Publication © 2013 Trustees of Dartmouth College. All rights reserved.